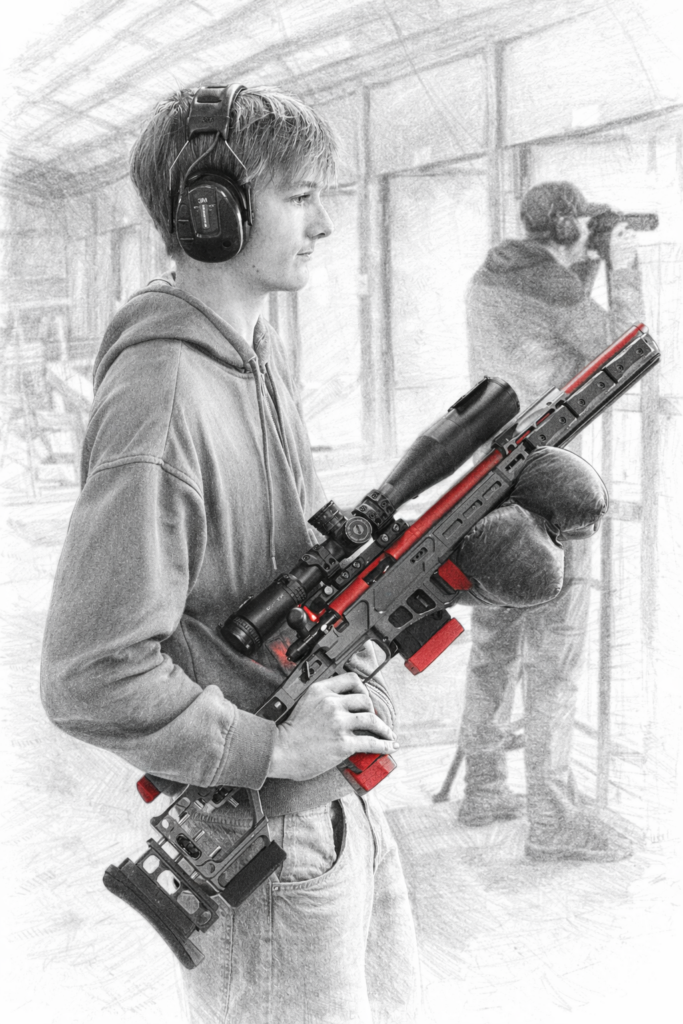

Barrel tuners tend to divide shooters. Some swear by them, others see them as unnecessary or even counterproductive. Rather than taking sides, we wanted to understand what is actually happening. When Jonas Sandberg asked us to test the JSP barrel tuner on our rimfire rifles, we approached it from first principles: how barrels vibrate, how tuners interact with that motion, and what changes can realistically be observed on target. This post covers the theory behind barrel tuners, what makes the JSP design different, and what we learned from a structured test on two very different rifles.

1. What a Barrel Tuner Is

A barrel tuner is an adjustable weight mounted at or near the muzzle of the barrel. Its purpose is to let the shooter change how the barrel moves while the shot is being fired, without changing the load, barrel, or action.

A tuner does not stop the barrel from moving. Every barrel moves when a shot is fired. What the tuner changes is the position and movement of the muzzle at the exact moment the bullet leaves the barrel.

From an engineering standpoint, a tuner changes the mass and inertia at the end of the barrel. That matters because the muzzle is the part of the barrel that moves the most during firing, and small changes there have an outsized effect on where the rifle is pointed when the bullet exits.

In simple terms:

A barrel tuner lets you adjust when in the barrel’s motion the bullet exits, without changing the ammunition.

2. Barrel Harmonics: What the Barrel Is Actually Doing

When a rifle is fired, several things happen at once:

- Pressure rapidly rises and falls inside the barrel

- The bullet is engraved by the rifling and accelerated forward

- The action resists that force while the barrel extends forward

- Gas exits the muzzle just after the bullet

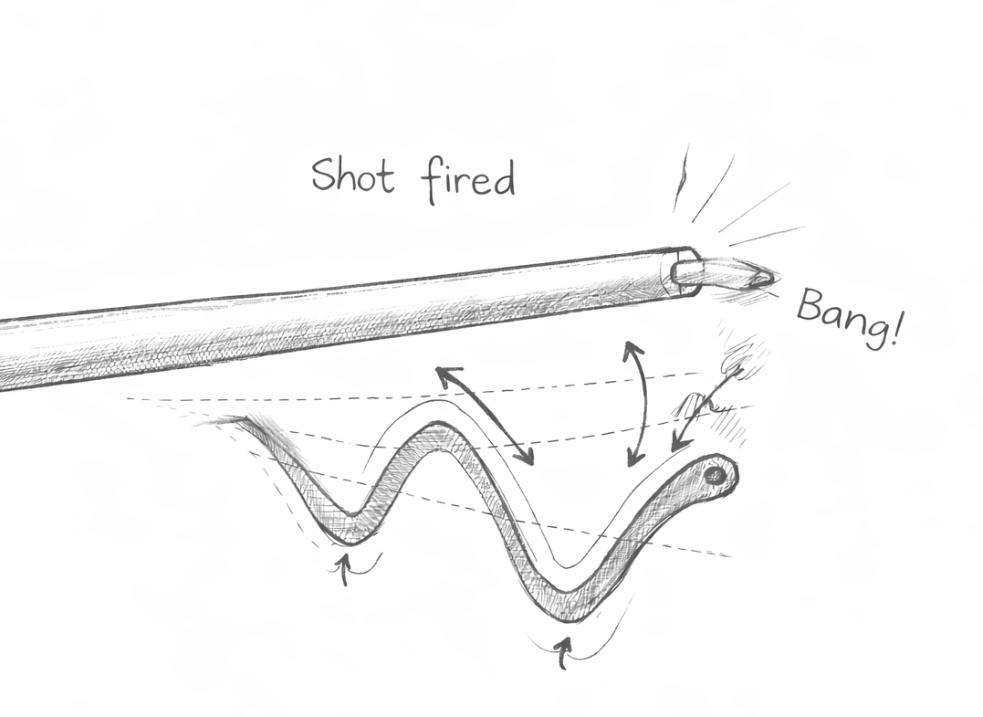

These forces cause the barrel to bend and vibrate, not unlike a steel ruler clamped to a table and flicked. This behavior is well described by classic beam vibration theory, which has been used in mechanical engineering for over a century.

A heavy PRS barrel behaves like a cantilevered beam: fixed at the action, free at the muzzle. When excited, it vibrates in predictable patterns called modes. The most important one for accuracy is the first bending mode, which dominates barrel motion during the short time the bullet is in the bore.

Two things matter most for accuracy:

- Where the muzzle is pointing when the bullet exits

The bullet goes exactly where the muzzle is pointed at that instant. Even very small angular differences show up as vertical or horizontal spread downrange. - How fast the muzzle is moving at that moment

A muzzle that is near the end of its movement (where it slows, stops, and reverses direction) is more forgiving than one moving quickly through the middle of its swing.

This is why barrels can show vertical stringing even when velocity numbers look “good enough.” Timing matters.

3. How a Barrel Tuner Works

A barrel tuner works by changing the timing of the barrel’s movement, not by changing the bullet.

Adding adjustable weight at the muzzle changes:

- How heavy the end of the barrel effectively is

- How fast the barrel wants to vibrate

- Where the peaks and valleys of that motion occur in time

What it does not meaningfully change:

- Chamber pressure

- Bullet exit time (which is driven mainly by velocity)

The bullet still exits at roughly the same time after ignition. What the tuner changes is what the barrel is doing at that time.

The goal is to adjust the tuner so the bullet exits when the muzzle is:

- Near the end of its upward or downward movement

- Moving slowly rather than quickly

This comes straight out of vibration theory: systems are least sensitive to timing errors near displacement extremes and most sensitive near zero-crossings.

That is why tuners can:

- Reduce vertical dispersion

- Make a rifle more tolerant of small velocity changes

- Allow a single load to shoot well over a wider range

And also why they cannot:

- Fix large SD or ES

- Make bad bullets shoot well

- Replace consistent ignition and fundamentals

A tuner adjusts timing sensitivity, not overall rifle quality.

4. Common Beliefs vs. What Physics Supports

“Tuners dampen vibration.”

They don’t, at least not in any meaningful way. Damping requires energy to be absorbed or dissipated. Tuners mainly add mass, which changes frequency and timing, not vibration amplitude.

“A tuner creates an accuracy node.”

The node already exists. It’s a natural result of how the barrel vibrates. The tuner lets you move that favorable timing window to line up with a given load.

“Heavy barrels don’t need tuners.”

Heavy barrels move less, but they still move. Lower movement does not eliminate timing sensitivity—it only reduces it. The same physics still applies.

“Once tuned, the rifle is always tuned.”

The tune is tied to bullet exit timing. Changes in velocity, temperature, or bullet design can shift that timing enough to matter, even if the tuner setting doesn’t change.

“Tuners replace load development.”

They don’t. Tuners can make a good load more forgiving, but they cannot make an inconsistent system truly accurate.

5. The JSP Barrel tuner

Jonas Sandberg, the creator of the tuner, is a well renowned benchrest shooter with medals both in Sweden and on the international levels. He has made and sold these tuners at competitions for some time, focusing on centrefire rifle systems. In December he reached out to us and asked if we would be interested in testing his tuner on our rimfire rifles which we of course agreed to. After the test we have shot them for a while and they certainly do their job nicely.

The design

The design of a barrel tuner is fairly simple on a high level. Typically we’re talking about a pipe that you thread on the end of your barrel, and on this pipe there is a threaded weight that you can move back and forth in the direction of the barrel to change it’s position. Usually there is a lock screw to fix it in place and it is not uncommon, especially on rimfire rifles, to use is as a barrel weight to help balance the rifle.

The JSP tuner is quite a bit different from other tuners we have seen, first of all, it’s tiny! The weight is only about 35 grams and it’s made of aluminium. Second it doesn’t have a lock screw and the funny thing is that it’s not needed since it’s almost impossible to move the weight in the first place. This is where the novel design comes in.

The weight is isolated from the barrel stem by two O-rings to create a more consistent reaction to the impulse of the shot through the barrel and the placement of the weight. This is the same principle as the bushings you use in engine mounts.

Damping effects of rubber elements: Elastomeric materials such as O-rings have viscoelastic properties that cause them to both store and dissipate energy under vibration. In the context of tuned mass damper systems, elastomer O-rings have been used as combined spring and damping elements to alter vibration response in flexible structures. The damping arises from internal friction in the rubber as it deforms, reducing the amplitude of resonant motion. This engineering principle supports the idea that a tuner with an elastomer interface can not only shift barrel harmonic timing but also dissipate vibrational energy, potentially reducing sensitivity to resonant peaks.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022460X18304693

The thread pitch for the weight is only 0.7mm meaning that a 20 degree movement of the weight gives you an incredibly small movement of weight (Keep that in mind if you use a suppressor on you rimfire rifle. What do you think happens when you fill that thing with gsr?).

If you are interrested in the JSP Barrel tuner contact Jonas via email on possarp@gmail.com

6. Test, Results and Interpretation

The test was designed to evaluate whether systematic changes in barrel tuner position produce measurable and repeatable changes in precision, while holding all other variables as constant as practical. The goal was not to statistically prove ultimate accuracy at any single setting, but to observe how precision responds as the tuner is adjusted through a continuous range.

Test Overview

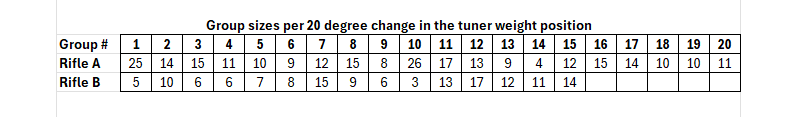

The barrel tuner used in this test features 36 index marks per full rotation and a thread pitch of 0.7 mm per rotation, corresponding to approximately 0.019 mm of axial movement per click. Testing began at a random tuner position. Between each shot string, the tuner was adjusted by two clicks (20 degrees, ~0.039 mm axial movement), always in the same direction to avoid backlash effects.

At each tuner position, two to three shots were fired. If clear imprecision was observed after two shots, the third shot was omitted and the test moved on. This approach reflects a practical reality: while small groups cannot prove precision, only a small number of shots are required to rule out an unfavorable condition. Around one full tuner rotation was tested for each rifle, resulting in approximately 15–20 evaluated positions per rifle.

Rifles Tested

Two rimfire rifles with very different characteristics were used.

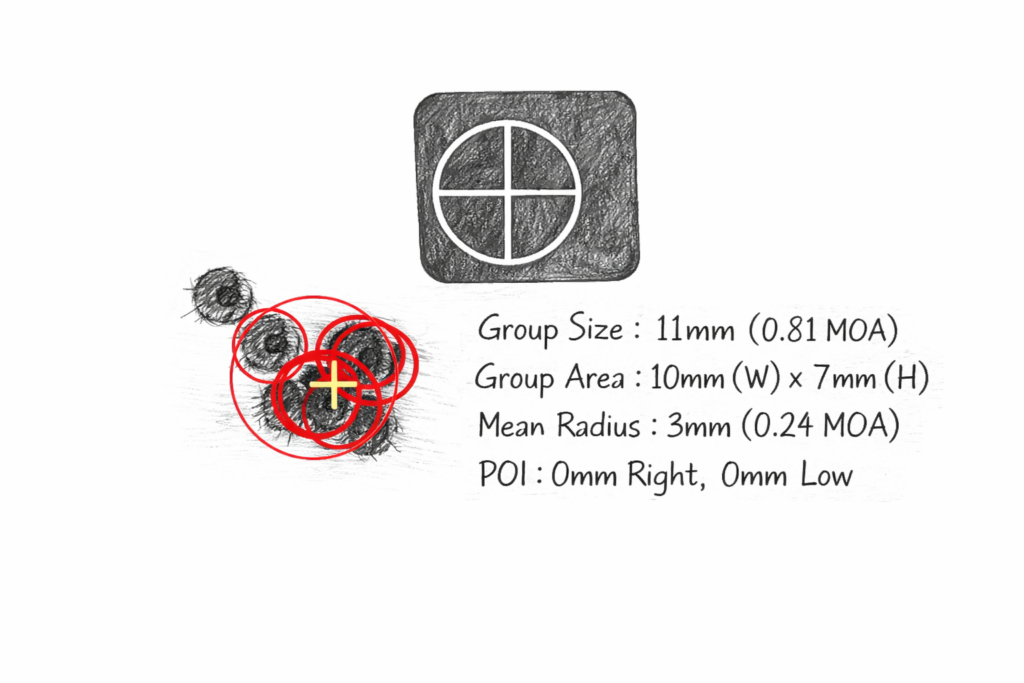

Rifle A (Noelle) was an Anschütz rimfire rifle with a shortened barrel and an original wooden stock. Anschütz barrels are typically choked at the muzzle, and shortening the barrel likely alters or removes part of this choke. As a result, this rifle represents a capable but mechanically compromised system, where barrel dynamics may no longer align with the original design intent. After tuning we changed the setting back to node 5 and shot a 10 shot control group of 15mm which is absolutely ok for this rifle.

Rifle B (Sander) was a Vudoo Three 60 with a heavy 46 cm barrel mounted in a rigid, weighted aluminum chassis. This rifle is a top-tier system that already demonstrates exceptional precision without a tuner. After tuning we changed the setting back to a node and shot a 10 shot control group with 9 shots within 7mm and a really annoying flier bringing the 10 shot group up to 11mm. Always that annoying flyer, amirite??

Observed Results

The results, summarized in the accompanying tables, show that group size did not vary randomly with tuner position for either rifle. Instead, both rifles exhibited structured variation in group size as the tuner was adjusted.

For Rifle A (Anschütz), group sizes ranged from very large groups (over 20 mm) at unfavorable tuner positions to markedly smaller groups (down to single-digit millimeters) at favorable positions. In this case, tuning produced a clear improvement in usable precision compared to the rifle’s baseline behavior.

For Rifle B (Vudoo), baseline precision was already extremely high. The tuner did not measurably improve the smallest observed group sizes. However, several tuner positions produced clearly worse groups than the rifle’s normal performance. This indicates that, even in a highly optimized system, tuner position has a real and measurable effect on precision.

7. Interpretation and Limits

The results of this test indicate that barrel tuner position has a real and measurable influence on precision in rimfire rifles. The magnitude and structure of the observed changes in group size are inconsistent with random dispersion alone and strongly suggest a mechanical cause related to barrel dynamics.

A key consideration in rimfire shooting is the lack of control over internal ballistics. Unlike centerfire rifles, rimfire shooters cannot adjust powder charge, seating depth, or ignition characteristics. Velocity and pressure behavior are fixed by the ammunition, and lot-to-lot variation is an unavoidable reality. In this context, a barrel tuner functions not as a fine-tuning tool for a load, but as a means of adapting the rifle’s barrel dynamics to a fixed ammunition profile.

The data shows that this adaptation can be meaningful. In the Anschütz rifle, which likely operates outside its original design condition due to barrel shortening, the tuner was able to shift the system into regions of improved precision. This suggests that a tuner can partially compensate for non-ideal barrel behavior when ammunition variables cannot be altered.

In contrast, the Vudoo rifle already exhibited excellent precision without a tuner. In this case, the tuner did not improve best-case performance, but it clearly demonstrated the ability to degrade precision when adjusted unfavorably. This reinforces an important limitation: a tuner does not inherently make a rifle more accurate. It alters the timing relationship between barrel motion and bullet exit, and that change can be beneficial, neutral, or detrimental depending on the system.

These findings also highlight a practical boundary. A tuner cannot correct fundamental ammunition inconsistencies, nor can it overcome large velocity spreads inherent to rimfire lots. What it can do is shift the rifle’s sensitivity to those variations by moving bullet exit into a more or less forgiving region of barrel motion.

Finally, it is important to emphasize the limits of the data. The use of two- to three-shot groups is sufficient to identify unfavorable tuner positions but not to define absolute accuracy. The results demonstrate cause-and-effect, not guaranteed improvement. In rimfire applications, where ammunition choices are constrained, a barrel tuner should be viewed as a system-level adjustment tool—useful in some rifles, unnecessary in others, and always dependent on careful evaluation rather than assumption.

8. Implications for PRS Shooters

The most important takeaway from this test is straightforward: a barrel tuner measurably affects barrel harmonics. The observed changes in precision were structured, repeatable, and large enough to rule out chance. That conclusion is independent of cartridge type. Any barrel that vibrates—and all barrels do—will respond to changes in mass and boundary conditions at the muzzle.

This matters for PRS shooters because barrel harmonics exist regardless of whether the rifle is chambered in rimfire or centerfire. The difference is not the mechanism, but the degree of control the shooter has over it. In centerfire rifles, handloading allows the shooter to adjust bullet exit timing through changes in velocity and pressure curves. In rimfire, that option does not exist. A barrel tuner addresses the same timing problem from the opposite direction: instead of changing the load to fit the barrel, it changes the barrel to better suit a fixed load.

The results also clarify what a tuner should—and should not—be expected to do. In a highly optimized rifle system with a stiff barrel, rigid mounting, and a well-matched load, a tuner may offer little or no improvement in best-case accuracy. This aligns with the experience of many top-level PRS shooters who already operate in a narrow, well-controlled accuracy window. However, the test clearly shows that even in such systems, unfavorable tuner settings can degrade precision. This confirms that tuners are not passive accessories; they actively influence barrel dynamics.

For rifles that are less than ideal—whether due to barrel contour, length, mounting constraints, or ammunition limitations—a tuner can provide meaningful benefit. By shifting the harmonic phase, it can move bullet exit into a region of reduced sensitivity, effectively widening the usable accuracy window. That benefit may show up as reduced vertical dispersion or improved tolerance to small velocity variations, rather than dramatic reductions in group size.

A practical implication is that tuners are best viewed as diagnostic and system-level tools, not guaranteed upgrades. Their value depends on the rifle, the ammunition, and the shooter’s willingness to test methodically. Importantly, tuners do not replace sound fundamentals, good barrels, or consistent ammunition. They cannot fix poor internal ballistics or shooter error.

Finally, this test reinforces a broader point relevant to PRS: precision is a timing problem. Whether that timing is adjusted through load development or through mechanical means such as a barrel tuner, the underlying physics is the same. Understanding that relationship allows shooters to make informed decisions about when a tuner is likely to help—and when it is simply another variable that must be managed.

Core Scientific References (Recommended)

- Dursun, T. (2017)

A review on the gun barrel vibrations and control for a main gun

This is the backbone reference. It establishes barrel vibration as a cantilever-beam problem, discusses vibration modes, boundary conditions, and summarizes decades of prior work. This supports barrel harmonics, modal behavior, and why muzzle conditions matter.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214914716301234 - Ahmed, N. Z. et al. (2020–2022)

Analytical and experimental investigation of internal ballistics and muzzle effects

Supports the claim that bullet exit timing is governed by internal ballistics (pressure curve, acceleration), not by external devices like tuners.

https://distantreader.org/stacks/journals/fumecheng/fumecheng-10686.pdf - “Effect of Barrel Tuner on Shooting Accuracy” (2023)

Directly investigates the effect of a barrel tuner modeled as added mass near the muzzle and evaluates its impact on vibration response and dispersion.

This supports statements about phase/frequency shift vs. damping and measurable accuracy effects.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369619299_EFFECT_OF_BARREL_TUNER_ON_SHOOTING_ACCURACY - Dai, C. (2024)

Study on the vibration response of an automatic rifle barrel during firing

Experimental measurements of muzzle displacement and velocity during firing using high-speed methods. This supports the importance of both muzzle position and muzzle movement rate at bullet exit.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1134/S0025654424605299

Upptäck mer från

Prenumerera för att få de senaste inläggen skickade till din e-post.